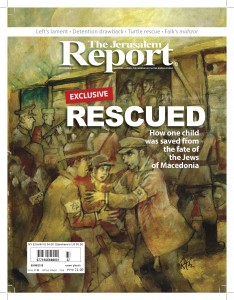

The discovery of mysterious WWII documents and a magazine article lead Ricardo to revisit how he was saved from deportation to Treblinka

Letter from Destiny

Bernard Dichek

Skopje, Macedonia, March 1943…

Bulgarian police bang on the door of the Asael home in the middle of the night.

They order Eliyahu and Denise Asael and their three-year-old son Sule to pack up their belongings and take them to a warehouse in a tobacco factory surrounded by barbed wire. They are held there along with the rest of Macedonia’s Jewish population of about 7,000.

Bulgaria, whose army has occupied Macedonia since 1941, has agreed to accede to the request of its Nazi ally and deport Macedonia’s Jews.

The Jews are held in squalid conditions for 10 days when freight trains pull up at the factory entrance. As the Asael family is being led towards one of the trains, Eliyahu sees a small group of Jews being released because, he is told, they have Spanish passports and Spain has requested their repatriation. Running as fast as he can with Sule in his arms, Asael catches up with an acquaintance called Moise Benadon and places his son in his arms.

This will be the last time Sule sees his parents. His mother is forced onto a train that takes her to the Treblinka concentration camp. His father escapes from the Skopje train station and makes his way across the border to Albania. But when he tries to return to Macedonia he disappears and is never seen again.

Sule becomes a member of the Benadon family. As the escalation in fighting makes it unsafe to travel outside the country, the family remains in Macedonia until the war ends. Afterwards, they immigrate to Argentina. Moise Benadon, who has a son of his own, eventually turns Sule over to his childless brother Salvador, who becomes Sule’s adoptive father and changes his name to Ricardo. When he is 11, Ricardo is told the story of how he survived, but he does not relate to the story.

Buenos Aires, Argentina, October 2014…

Ricardo Benadon, 74, a retired architect and father of three, reads an article that I wrote in The Jerusalem Report entitled “The 28 envelopes” (September 22).

The article, based on an interview I conducted with Macedonian researcher Jasmina Namiceva, describes mysterious envelopes she discovered a few years earlier in the national archives. The envelopes, bearing the insignia of the National Bank of Bulgaria, are labeled with Jewish names and contain coins and jewelry.

Namiceva points out that during the deportation the Bulgarian police took the Jews’ last remaining possessions away from them. She suggests that the discovered envelopes may have belonged to the Jews with Spanish passports. In the turmoil, says Namiceva, they may not have been able to get their possessions back.

In an attempt to locate the owners of the envelopes, I conclude the article with a list of the names. One of them is Moise Benadon.

“It was a very emotional moment for me,” says Ricardo Benadon, as he describes reading the article. “Seventy years had passed and I had completely blocked out the events.”

Benadon decided the time had come to return to his hometown. “I wanted to see the envelope and pay tribute to my parents,” he tells me when I interview him during his visit to Skopje in April. “I also wanted to pay homage to Moise Benadon, the man who saved my life.”

During his visit, Namiceva accompanies him to the Monopol tobacco factory, where the current owners, Imperial Tobacco, preserve one of the wooden warehouse rooms in the exact condition it was in during the war when the Jews were crammed in there.

“I can feel the energy of the people who passed through here,” says Benadon as he walks across the haunted hall. When Namiceva shows him the envelope belonging to Moise Benadon, he is overwhelmed with feelings. He holds the envelope to his face and kisses it.

The Benadon envelope is completely empty. “It doesn’t matter, it really doesn’t make a difference to me,” says Ricardo as he carefully examines Moise Benadon’s handwriting on the cover. Namiceva shows him the contents of some of the other envelopes. Among them: Turkish lira coins, a gold-plated bracelet and a child’s earring.

Namiceva next accompanies Ricardo to the Church of St. Clement. In preparation for his trip, Ricardo had dug up a memoir written by the late Jacques Benadon, the son of Moise who was a teenager during the war. In his memoir, Jacques described another incident that Ricardo had blocked out of his mind.

“After Moise Benadon left the tobacco factory, he realized that because he didn’t have any documentation for me, it was a dangerous situation,” explains Ricardo, referring to Jacques’ recollections. “So he decided to place me in a Catholic orphanage. However, two weeks later, he changed his mind and decided to risk taking me back. But when he returned to reclaim me the nuns were reluctant to give me up.”

Now it was Moise Benadon’s turn to run fast. When no one was looking, he scooped up Ricardo into his arms and fled.

Namiceva had tried to locate the orphanage, only to find out that it no longer existed. However her inquiries led her to Monsignor Cermontik, 84, today the head of Skopje’s Catholic Church. During the war, the Cermontik often visited the orphanage and played with Jewish children hidden there.

It’s possible that one of them was Ricardo. He recalls a number of the Jewish children. “There was one called Eliezer, another called Yehuda,” he says pronouncing their names with an uncannily perfect Hebrew accent.

Namiceva, who is of Armenian heritage, did not intend to delve into Macedonia’s Jewish past when she first began to sift through archive boxes in 1999.

An architect by training and employed as a curator of the Skopje City Museum, her original goal was to find documents relating to the buildings destroyed in the Skopje earthquake of 1963.

“A vital part of Skopje’s Old City was the Jewish Quarter which was completely destroyed,” she observes, noting that Jews had been a prominent part of Skopje life since the 16th century. Most came from Turkey and Greece and were of Sephardi origin. Among them were a number of families who had taken up Spain’s offer of Spanish citizenship to Sephardi Jews in the 1920s and obtained Spanish passports while continuing to live in the Balkans.

Her research into the old Jewish buildings soon gave way to an interest in the Jewish way of life. She became friends with a handful of elderly Macedonian Jews who survived the deportation by fleeing beforehand to join the Yugoslav resistance. With one of the survivors, Yamila Kolonomos, she even co-wrote a book, “Sparks of the Macedonian Sephards”. The book, which came out in three languages, Ladino, Macedonian and English, describes the history of Macedonia’s Jews and includes traditional recipes and colorful folk proverbs.

When Namiceva came across the voluminous documents the Bulgarians kept about their Jewish subjects, she shifted her research focus to the wartime era. Prior to deporting the Jews, the Bulgarian officials forced them to wear yellow badges and confiscated all their financial assets. Consequently when a Jewish family required money to buy something they had to fill out forms and seek permission to withdraw funds.

“The forms evoke a very detailed description of each family,” she explains. “You can picture the scene as you read about someone with an ailing father requesting a small amount of money for medicine, another who wants to buy a bicycle for a child.”

Studying the records of more than 600 Jewish families, Namiceva estimates that she perused more than 25,000 pages of documentation.

“I sometimes had the feeling that the persons mentioned had become a part of my daily life, bit by bit becoming close to me,” she recalls. “That’s why the day I discovered the envelopes, I felt like they were traces of my own personal tragedy. The other researchers in the room around me thought that I had become mad, sitting there, crying over some old worn-out papers. They simply couldn’t realize how deeply I was touched by the destinies of the people whose names were written on the envelopes.”

Ricardo’s testimony and those of other families connected to the envelopes (see “Survival sagas “sidebar), verifies Namiceva’s theory about the origins of the envelopes. The story of Ricardo’s rescue also raises the unresolved question of the extent to which the Jews were aware that the labor camps they were told about by the Bulgarians were really death camps.

Would Ricardo’s father have been willing to give up his only child if he thought that their destination was just a labor camp? What went through his mind when he spotted Moise Benadon?

By March 1943, during the time of the Macedonian deportation, the Treblinka gas chambers had already been in action since July 1942 with Warsaw ghetto deportees as the first victims. The Nazis continued to insist that Treblinka was a labor camp, and the Allies, even if they had intelligence information to the contrary, failed to spread the word.

Consequently, what the Jews sequestered in the Skopje tobacco factory in March 1943 knew and didn’t know – along with the other Jews being rounded up throughout Europe at that time – remains one of the great unresolved questions of the era.

Regardless of what Eliyahu Asael knew or didn’t know, Namiceva tells Ricardo when the topic is raised, “he would have been a very brave man to have acted to save your life.” She points out that the Bulgarian army lined up three rows of soldiers behind the fence surrounding the factory. “It was a very difficult situation and very few people tried to disobey or escape.”

For Ricardo Benadon, the trip to Skopje helped him come to terms with his past. He also felt that it was important that his son Patricio accompany him on the journey. “It will ensure that the family story continues to be passed on,” he notes.

For Jasmina Namiceva, who had spent years looking at names on pieces of paper and trying to imagine the faces behind those names, Ricardo had literally brought history to life. It was the ultimate reward for discovering an important piece of historical evidence.

“It was a touch of destiny that I would be the one to open the box (of the envelopes). It’s something that happens to a researcher once in a lifetime,” she concludes.

HEADLINE FOR SIDEBAR:

Survival sagas

In addition to Ricardo Benadon, I have so far located about 12 families named on the envelopes.

Several pointed out that because there are so few Macedonian survivors and their descendants their unique history has often been overlooked in chronicles of the Holocaust. Indeed Macedonia’s Jewish community was perhaps the single most devastated Jewish population in Europe – more than 99 percent of its members were annihilated.

The community may have been small in size – the equivalent of a single Polish shtetl – but the Macedonian Jews remain proud of their heritage – a blend of Sephardi Ladino, Serbo-Croatian and other Balkan influences. With the discovery of the envelopes, they are pleased to finally gain a bit of acknowledgement.

One of the survivors is Avraham Saporta, 78, who today lives in Venezuela. The names of his father, Isak Saporta and his grandfather Jakov Avram Saporta both appear on the list of envelopes. “Reading the article about the envelopes unleashed a torrent of memories for me,” says Avraham Saporta, 78, who was six years old when his family was spared on account of his father’s Spanish passport.

Saporta’s face lights up when he hears the story of Ricardo (Sule) Benadon’s rescue. “Sule and I used to play together,” recalls Saporta, noting that his family, like Ricardo’s adopted family, continued to live in Macedonia until after the war. “I haven’t heard from him since,” relates Saporta, during a recent visit to Israel. “Now I can’t wait to contact him.”

Among the Macedonian survivors who immigrated to Israel was David Asher Bitty and Asher David Bitty the father and grandfather respectively of Mira Zachor and Orly Bitty. “Our father’s troubles did not end with his release from the Skopje detention camp,” says Zachor, who was born in Israel. “He told us about how he was taken to the Ihtiman labor camp in Bulgaria where he was forced to work in a gravel quarry for six months. Later he was tortured by the Bulgarian police after he was caught helping the Partisans.”

As Orly Bitty displays photos of their grandfather’s sister Mary David Bitty and of one of their aunts Nina Simon, she notes that these relatives were deported to Treblinka despite the fact that they at one time had Spanish passports.

“They had married men who did not have Spanish citizenship and a woman’s citizenship was determined by her husband, and in this case, also her fate,” explains Bitty, who works for Na’amat, a women’s rights organization.

B.D.

HEADLINE FOR SIDEBAR: The murky role of Boris and Franco

One of the most contentious issues related to the deportation of Macedonia’s Jews concerns Bulgaria’s part in the tragedy.

For many years, the Bulgarian government, emphasizing that not a single Jew from within the borders of Bulgaria was deported, contended that it had an unblemished wartime record. Indeed Bulgaria was the only occupied European country whose Jewish population actually increased during the war – from about 48,000 to 50,000.

Bulgaria defended the deportation of Jews from its annexed territories – 7,148 from Macedonia and about 5,000 from Thrace (northern Greece) – as being forced by the Nazis. In 1994, King Boris III, Bulgaria’s wartime ruler, was even honored in Israel by the Jewish National Fund when it decided to plant a forest in his name.

But as more and more historical research has come to light, a contrasting view of Bulgaria’s conduct has emerged. In March 1943 plans were underway to deport the Jews of Bulgaria along with those of Macedonia and Thrace. In a decree signed jointly by Boris and the Bulgarian cabinet, the first 8,000 Bulgarian Jews to be deported were to be put onto trains during the same two-week period that the Macedonian and Thrace Jews were transported to Poland.

However after protestations by Bulgarian church leaders, parliamentarians, artists and other groups, Boris desisted and settled for sending able bodied Jewish men to labor camps where they worked on railroad construction. But the government did not rescind the orders to expel the Macedonian and Thrace Jews and seize their property, the proceeds of which were transferred to the National Bank of Bulgaria. In 2000, an Israeli public committee concluded that the Bulgarian leadership be held responsible for the Macedonian and Thrace deportations. The forest memorial honoring the Bulgarian monarch was subsequently removed.

Equally controversial, has been Spain’s wartime legacy – especially that of General Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain from 1939 to 1975.

During World War II, Franco declared Spain to be neutral. When the Nazis invaded France, he allowed French Jews who fled to the Spanish border to enter Spain – unlike the Swiss who refused to let them cross into Switzerland.

Franco also was credited for saving the lives of Jews like Moise Benadon, who were deferred from deportation on account of their Spanish citizenship – not only in Macedonia but in other countries like Hungary and Romania as well. Tributes to Franco have included former prime minister Golda Meir thanking him for “the humanitarian attitude taken by Spain during the Hitler era, when it gave aid and protection to many victims of Nazism.”

But this view has been undermined by revelations that Franco maintained a secret list of the 6,000 Jews in Spain that he intended to turn over to the Nazis once the Germans had secured their victory. Equally damning has been evidence indicating his failure to act when Spanish diplomats across Europe requested assistance in their efforts to save the Jews with Spanish passports.

That evidence indicates that were it not for the initiatives of local Spanish diplomats, it is unlikely that the Jews with Spanish passports would have been protected.

That also was the case in Macedonia where Julio Palencia, Spain’s ambassador in Bulgaria, who was also in charge of the annexed territories of Macedonia and Thrace, intervened on behalf of the Jews with Spanish passports. Palencia repeatedly appealed to his superiors in Madrid for permission to issue the visas – but his requests were ignored.

Finally, he took the matter into his own hands and only after he granted the visas did he report doing so. So zealous was Palencia in taking other measures to save Jews, that the Bulgarians declared him to be persona non grata. He was subsequently expelled to Spain where he was reprimanded.

B.D.